(by Bruno Kneubühler)

General Informations

- the climat at Capilla del Monte is characterized by warm, rather dry summer and cool to cold, semi-humid winter (see Climat Data Org)

- adult specimens were collected in November 2015 by José Alejandro Borquez (AR). He reported that their natural habitat is sandy and of intermediate moisture

- ID by Oskar Conle (DE)

- F1 CB culture in 2017 by Bruno Kneubuehler (CH)

F2 CB culture in 2019 by Bruno Kneubuehler (CH) - further taxonomical informations ➤ Phasmida Species Files

- for the moment this culture won't be spread to other breeders. Firstly because the procedure to breed Agathemera is not yet fail proof, and also because of their suspected pest potential in Europe

Females

- sturdy, stubby

- body length ≈ 6.5 - 7 cm

- reddish-brown

- a pair of bigger lobes (1) on the mesonotum. Though they look like small wings, they are anatomically no wings. These lobes are called mesonotal lobes (A. Camousseight) or mesoscutellum lobes (O. Conle). The female can make a squeaky sound with these lobes

- there is another pair of smaller lobes (2) on the metanotum, which are (as of yet) not taken into taxonomical consideration. These would be called metanotal lobes

Males

- sturdy, though not as stubby as the females

- body length ≈ 4 - 4.5 cm

- reddish-grey

- a pair of bigger lobes (1) on the mesonotum. Though they look like small wings, they are anatomically no wings. These lobes are called mesonotal lobes (A. Camousseight) or mesoscutellum lobes (O. Conle). The male can make a squeaky sound with these lobes

- there is another pair of smaller lobes (2) on the metathorax, which are (as of yet) not taken into taxonomical consideration. These could be called metascutellum lobes

Nymphs

- freshly hatched nymphs are grey-brown and ≈ 14 mm long

- distinguishing male and female nymph is possible in L1, though it will be easier at later nymphal stages

- on how to distinguish between male and female nymphs

Eggs

- ≈ 8.5 x 3.5 mm

- dark brown to blackish

- slightly verrucous surface

- micropylar plate framed by a light colored border

- eggs are rather big, compared to the female's size

- here a female and all the eggs she laid in just about one month!

- average weight of an egg is about 0.055 g (F1 generation)

- although the females stick their eggs quite deep into the soil, the egg shell is quite frail. The shell breaks easily, which is quite astonishing for an egg-burying phasmid species. An short animation of a female laying her eggs.

- upon being laid, the eggs are coated by a sticky substance. Thus the surrounding sand will stick to the eggs (while the sticky substance dries up), so that they are entirely covered with sand / soil if unburied

- if eggs are incubated straight away, there is no need to remove this sand /soil layer. Yet if one intends to transport the eggs, it is advisable to remove the sand layer, in order to protect the quite brittle egg shell

- very interesting morphological study on the eggs of Agathemera > CUBILLOS et al. 2020 5)

Tested Food Plants

food plants on which this species thrives

- Rhus typhina

- (coll.) staghorn sumac

- very well accepted by nymphs and adults

- summergreen, leaves appear quite late in spring

- this was a common garden plant some decades ago. Now it is considered to be an invasive neophyte, and is on the watch-list in most parts of Europe or even forbidden (like here in Switzerland)

- quite probably other Rhus species are equally well accepted

- smoke tree (Cotinus coggygria)

- (coll.) european smoke tree or smoke tree

- very well accepted by nymphs and adults

- summergreen, leaves appear quite late in spring

- native in southern Europe, and quite a common, non-invasive garden plant in the more temperate parts of Europe

- when given the choice, they prefer Rhus over Cotinus. Nevertheless it is possible it is possible to switch back and forth between both plants

- Cotinus leaves appear a bit earlier in spring than Rhus leaves, and they do also last longer in late autumn. Thus Cotinus extends the "vegetation period" for Agathemera by about 4 weeks (here in Switzerland)

- Lithraea molleoides (Anacardiaceae)

- well accepted (Gabriel Rodriguez (AR), personal communication)

- this might be one of the natural food plants

plants which are well accepted (by all stages), yet A. luteola "Capilla del Monte" does not thrive too well on:

- Pistacia lentiscus

- (coll.) lentisk or mastic

- available as (poison-free) evergreen greenery in flowershops, where they just call it "Lentiscus" (or similarly)

- well accepted, but A. luteola "Capilla del Monte" do not thrive well on this plant

- many L1 nymphs die just before or during their first moult, even though they look healthy and well fed. Few nymphs only make it through the first moult successfully, when fed on this plant. Of about 15 nymphs which have been fed on Pistacia lentiscus as the sole food plant in L1, only one pair made it to the subadult stage. Subsequently this subadult pair has been fed on Rhus typhina, to be on the safe side.

- our impression is, that Pistacia lentiscus might be too nutritious. Cause nymphs appear to be really fat just before they die. And most L1 nymphs do not make it through the first moult

- thus we consider Pistacia lentiscus not to be a healthy food plant option, at least not during their developement

- but this plant could be a food option, offered in the middle of their hibernation. Especially if they would not make it throught a full 6 - 7 months hibernation period (more on this, see below). To be tested

- Filipendula ulmaria

- (coll.) meadowsweet or mead wort

- Filipendula ulmaria is a very common herbaceous, summer-green plant in Europe

- well accepted by freshly hatched and older nymphs

- when given the choice, they prefer Cotinus over Filipendula (and Rhus over Cotinus)

- though they feed so well on this herbaceous plant, a substantial portion of the nymphs will die after some weeks. Even though they look healty and well-fed

- specimens fed with Filipendula seem to grow slower compared to specimens fed with Rhus or Cotinus. Is Filipendula less nutritious, or does it even contain an inhibitor which affects their developement?

- Hypericum hidcote

- (coll.) Hypericum

- very well accepted by freshly hatched nymphs, but they die very quickly (within 1 - 3 days). This plant seems to be poisonous for them

plants which are not accepted:

-

Salal (Gaultheria shallon)

Untested, yet potential food plants for Agathemera

these plants have been reported to be accepted as food plants for different (!) Agathemera species. Please note that for the moment there are no further solid, first-hand information available whether these food plants are accepted at all (by any Agathemera species) or could support a healty CB population. See our sobering experiences above, with plants which are well accepted (e.g. Hypericum, Filipendula), yet turn out to be noxious or unhealthy for Agathemera luteola "Capilla del Monte"

- Acaena (Sanguisorbinae, source: Camousseight 1, reported as the natural food plant for Agathemera crassa)

- Citrus (Rutaceae, DiBlasi 3)

- Geranium (Geraniaceae) (Daniel Rojas Lanús [AR], pers. comm.)

- an insect dealer from Chile reported that A. crassa accepts Geranium spp.

- Pelargonium (Geraniaceae), commonly known as geraniums, pelargoniums, or storksbills, is not accepted by L1 A. luteola "Capilla del Monte" nymphs (B. Kneubühler, 2019)

- Hoffmanseggia (Fabaceae, DiBlasi 3)

- Mulinum (Apiaceae, source: Camousseight 1, reported as the natural food plant for Agathemera crassa)

- Larrea (Zygophyllaceae, DiBlasi 3)

- Lecointea (Fabaceae, DiBlasi 3)

- Schinus (Anacardiaceae, Gabriel Rodriguez (AR), Daniel Rojas-Lanus (AR), personal communications)

Basic behaviour, biology, breeding

- please note that the following observations have been made under CB conditions (unless otherwise stated)

- active mainly during the night. Exept for adult males which have not yet found a "free" female. These males wander around restlessly during the day too

- nymphs are quite gregarious, and often on top of each other during the day. Whether adults display the same behaviour, that I could not yet observe, as the number of adults I had was low

- neither nymphs nor adults hide on the ground during the day, even if there are dry leaves or bark available for them to hide away underneath

- nymphs moult about every 3 weeks (at 20 - 23°C), only the last moult takes a bit longer (4 weeks). Males are adult after about 3 months, females after 3.5 - 4 months. As in other phasmid species, Agathemera females have one more moult than males

- Agathemera are famous throughout Argentina and Chile for their smell, which some call "stink". Therefore they're called Chinchemolle, or sometimes also Chinchemoye, Chinchemoyo or Tabolango. Chinchemolle means something like stinky beast or bug

- it is their (colorless) defensive spray, excreted from prothorax glands, which is smelly. And it is hard to describe that scent. It has a strong metallic, chemical note, is pungent, reminds me a bit of garlic, but does not smell rotten or putrid. Most people perceived it as somewhat unpleasant. The only just description is - they smell like Agathemera. And if one breeds Agathemera indoors, then it might well be that this quite persistent "fragrance" fills the whole appartement at times. A seperate room, with a more or less sealed door, is a good idea - unless you live in cottage out in the forest

- the defensive spray of Agathemera elegans has been indentified as 4-Methyl-1-hepten-3-one 4). The defensive spray of other Agathemera species have not yet been analysed

- when handled carefully, (captive bred) Agathemera luteola "Capilla del Monte" do not use their defensive spray, neither nymphs nor adults. One really has to hassle them quite a bit before they will release it. This could be observed for L2 and older specimens, while the L1 specimens do not stink at all. Whether this behaviour is the same for wild Agathemera luteola "Capilla del Monte" (or other Agathemera species), that is unknown for now

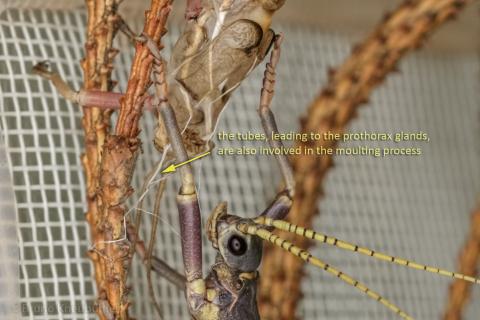

- but they do use or release their spray always just before moulting. Whenever I have noticed that smell, then a nymph moulted during the following 1 - 2 nights. So releasing their spray is also connected with the moulting process. Potential explanations for this behaviour:

- to fend off of potential predators during that crucial time

- yet on the other hand there are predators (like owls and other birds) which prey on Agathemera. So the smell could attract potential predators

- to warn other Agathemera, as not to disturb the specimen which is about to moult during it's moult, which is a very vulnerable situation

- the tubes which lead to the prothorax glands are also involved in the moulting process (see photo on the right of a male just after his moult to be subadult). Thus to empty their prothorax glands, could support the moulting process to be smooth and successful (pic 1, pic 2)

- this "pre-moult" smelly phase is especially obvious for older nymphs (L3 and older). This is no surprise, as they are bigger and their prothrax glands contain more secretion than younger specimens

- we were experimenting with possible solutions on how to get the stinky situation under control:

- installing a suction ventilator, which transports the air in the Agathemera room directly out of the building. This is the most effective method for me, but one might have to make a hole in the wall

- an organic air freshener (to counteract the smell). This does not really work too well, as the air freshener's fragrance just overlays the "bad" smell

- keeping the whole Agathemera cage in a tightly closed plastic bag does significantly reduce the intensity of the smell. But the humidity in the bag (and thus in the cage) rises too high, which seems to be quite unnatural for Agathemera. Even though this high humidity can be controlled with silica gel (to reduce the air humidity) to some degree, the mortality rate in such an "air-tight" cage was higher than in a "normal" cage. Thus this method is not only time-consuming to be maintained, but it does not support healthy breeding conditions

- the smelly secretion might also have positive sides, nevertheless. The patagonian natives (Tehuelche) applied crushed Agathemera (maybe A. claraziana or A. millepunctata) as a cure onto wounds and tumors (thanks to Daniel Rojas-Lanús [AR] for this info, translated from Camousseight 1995). So maybe it has a beneficial effect, when the breeder inhales the smelly odors at times?

- nymphs stop feeding 2 - 3 days before they moult. During that time they hardly move about, often stay in one and the same place day and night. Exept for the night when the moult is actually going to happen. Then they search for the right place for moulting

- the smell male nymphs produce prior to their moult is considerably less pungent than the female's. This could be due to their smaller size, thus the quantity of defensive spray in their glands is less

- rural legends from Chile and Argentina (also stated in scientific articles) claim that the Agathemera's defensive spray can irritate the eyes of a potential predator (e.g.human eyes), and even cause temporary blindness. So far, I have not had any personal experience which would support this allegation. Gotta admit though, that I have been careful

- at least adult males can also squirt a clear liquid (from their prothoracic glands?) when hassled, but astoundingly this is odorless. This makes me wonder whether that famous "stinky smell" is at all connected with the "regular" defensive spray. Or might it be that this "stinky smell" is be predominantly connected with the moulting process?

- adult males and females can make a squeaky, twittery sound

- this is unlike any sound produced by a phasmid I have heard so far

- they produce this sound by rubbing the mesoscutellum lobes against the (underlaying) metanotum

- so far I have heard subadult and adult males and adult females producing this sound

- another extraordinary and as of yet unknown behaviour and ability is that A. luteola "Capilla del Monte" nymphs and adults can elongate their body. This behaviour manifests in different ways:

- right after a moult A. luteola "Capilla del Monte" nymphs are substantially shorter than about two weeks later, just prior to their next moult. For example, a subadult female nymph just after moulting is about 4.5 cm. About 2 weeks later she already measures about 5.9 cm, which is an elongation of about 1.4 cm or about 33% ! This phenomenon can also be observed in other phasmid groups, although not to this degree

- but nymphs and adults can manifest this behaviour "at will" too. When one carefully and softly presses on their thorax, then they instantly elongate their body. For an adult female this elongation can be around 0.5 cm, which is about 8% of the non-elongated length. This behaviour has not been reported so far, and this has not been observed in any other phasmid group. This ability could explain why Camousseight found quite a wide range of lenght differences amongst nymphs of A. mesoauriculae. It is rather difficult to accurately measure the length of an Agathemera, as they are often quite restless. So if one measures a restless specimen by fixing it with some light pressure, then it will expand and thus appear to be longer than a calm specimen

- Possible explanations for this elongation capacity:

- it offers a substantial potential for "growth" within each nymphal stage

- this enables them to flatten their body and thus to hide out in narrower gaps in the ground, under bark or stones during the day or during winter time (hibernation)

- this enables females to bury their eggs a bit deeper into the ground, which could be a slight advantage in areas where freezing temperatures during winter time and / or severe droughts might occur. Obviously eggs which are buried deeper into the ground are better protected

- as a female can lay up to 10 big eggs in one night only. Thus being able to expand her abdomen creates some "extra space" within here body, where she can store eggs until the next egg-laying cycle

- males are almost always on the female's back. Usually they are "coupled-up", in the mating position. Just from time to time they "uncouple", and that is when the female is about to lays eggs. It looks as if she can not lay eggs, when the male is coupled-up

- females lay their eggs in clutches, and stick them deep into sand / soil

- short animation of egg laying process on Youtube

- first eggs are laid about 5 weeks after the adult moult

- females stick their abdomen deep into sand or soil, then their body is underground almost up to the hind legs. Like this they can bury the eggs some 3 cm deep into the ground

- eggs are fully covered with sand / soil afterwards, that sand is somewhat glued to the eggs. Thus the eggs must be covered with some sticky coating when being laid, which then dries up and glues the sand to the eggs. This coating with sand could offer the eggs some protection aginst mechanical damage, or to anchor them in the soil

- the sand which covers the eggs can be removed very gently

- around 2 - 10 eggs per clutch

- over 3 - 5 days, a female deposit several clutches of eggs, the first one usually is the biggest (5 - 10 eggs) while the following clutches are usually smaller (1 - 5 eggs)

- up to 40 eggs per female and month. This is quite an amazing amount comparing egg and female's sizes. 40 eggs correspond to about 50% of the females weight. A female with all the eggs she laid in about one month only!

- they lay an egg clutch roughly every 2-3 weeks (when fed on Rhus typhina)

- females even lay some eggs during their hibernation

- eggs of this species are quite prone to get mouldy, if kept too moist (maybe also true for other Agathemera species)

- moulting happens during the night, during which they hang from all their 6 legs

- males will be adult after about 3 months (at 20 - 24°C), females after 3.5 months

- seperate adult male from young females, as they start to "hassle" subadult females

- Agathemera luteola "Capilla del Monte" are rather clumsy climbers. Nymphs and adults show some difficulties to climb on plastic, which is no problem for most phasmids.

- adult female can hardly climb plastic or glass walls anymore, as they are too heavy

- Agathemera luteola "Capilla del Monte" nymphs, adults and eggs hibernate out in nature. Nevertheless a contact saw Agathemera (maybe A. millepunctata) feeding even when their habitat was snow-covered (Richard D. Sage, USA)

- easy to breed, when food plants are available

- keep nymphs seperate from adults

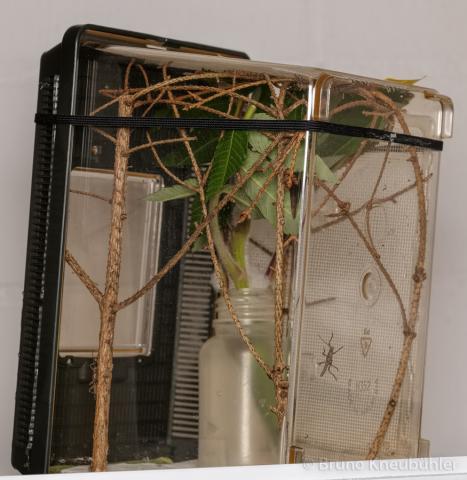

- use cages with big ventilation areas. Closed, or almost closed cages are no good choice for keeping Agathemera.

- their (so far known european) substitute food plants are not ever-green plants. Thus in spring they regrow, and these fresh, tender sprouts are quite delicate for some weeks. They are especially vulnerable to desiccate / wither quickly. During this time, keep the Agathemera cage a bit more humid, by reducing the ventilation areas. But do NOT keep a humid or even wet soil / paper in the cage. Basically to much additional humidity (rH) can harm the Agathemera culture. So as soon as the new food plant sprouts are strong enough, then again increase the ventilation areas to their maximum

- no additional humidity humidity for nymphs or adults. A humidity of around 60% rH or even below seems to be good enough

- so never spray them with water and do not add any humid substrate in the cage

- small nymphs can be kept in a Faunabox (or a similar cage), which shall not be too small

- provide a cage of about 30 x 30 x 30 (cm, L x B x H) for 3 - 4 adult couples

- provide the adults with a cage with a thick sand layer on the floor (at least 3 cm deep), so that the females can stick their eggs deep into the sand (see an animation of the egg-laying process on Youtube)

Egg incubation and hibernation

- incubation of Agathemera luteola "Capilla del Monte" eggs is more elaborate than in other phasmids

- experiences so far suggest, that these eggs need to undergo alternating warm and cold ("summer / winter") periods. Their total incubation time is 2+ years, after 2 summer / winter periods

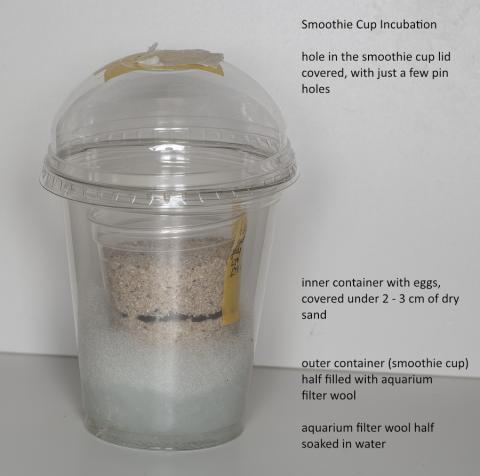

- if the eggs are in direct contact with a humid incubation substratum (e.g. vermiculite), then they get mouldy quickly. So made sure, that the eggs are not in direct contact with a humid substratum during incubation. Our arrangement we call the Smoothie-Cup-Incubation (which could actually be used for incubation of other phasmids too):

- you need a bigger smoothie cup, a smaller plastic cup, some dry sand and aquarium filter wool

- put eggs on dry sand in a small plastic container without a lid, and cover them with 2 - 3 cm of dry sand

- put this container in a larger plastic container (smoothie cup) with a tightly closing lid, and which is at least half filled with aquarium filter wool

- fill water in the bigger container, so that half of the aquarium filter wool is soaked in water

- the advantage of aquarium filter wool is, that is it non-organic and thus it won't get mouldy. And it does not absorb any water, so it's surface will stay dry

- make some pin holes in the lid of the outer plastic container. But only just enough, so that no condensation water will accumulate on the sides of the container

- CB incubation cycles:

- phase 1: RT incubation (≈ 1 - 4 months) until the end of September (RT = room temperature)

- phase 2: hibernation (≈ 5 months) until the end of February (2 - 4°C)

- phase 3: RT incubation (≈ 7 months) until end of September

- phase 4: hibernation (≈ 5 months) until end of February (2 - 4°C)

- phase 5: RT incubation (≈ 7 months) until end of September, nymphs will start hatching about 1 - 2 months after RT incubation has resumed

- phase 6: hibernation (≈ 5 months) until end of February (2 - 4°C)

- phase 7: RT incubation (≈ 7 months) until end of September, nymphs will start hatching about 1 - 2 months after RT incubation has resumed

- if need be (no yet any hatching, or yet unhatched eggs), continue with 4. phase

- experice over 2 generations shows that:

- only 2 nymphs hatched during phase 1. At that time, these eggs were incubated for about 5 - 6 months at RT and had not undergone any hibernation

- a few nymphs were hatching during phase 3 (after 1 hibernation period)

- many nymphs were hatching during phase 5 (after 2 hibernation periods)

- many nymphs were hatching during phase 7 (after 3 hibernation periods)

- this indicates, that nymphs of A. luteola (Agathemera in general?) are preferably hatching after at least two hibernation periods.

- these observations suggest that the total incubation time is 2+ years

- nymphs always hatch during the night

- it is common that some nymphs will hatch weeks or even many months (if not years) after the first nymphs - from the very same batch of eggs

- if some nymphs will hatch too early in spring, and their food plants do not yet have any new leaves, then just put them again back in the fridge at around 5°C. They should do well for another 2 - 4 weeks at low temperatures.

- tested incubation temperatures:

- 9 - 12 °C results in a high hatching ratio

- 2 - 4°C results in a high hatching ratio

- for the moment it is unknown, whether a high humidity during incubation is necessary. Yet the experiences gained so far show that incubation works quite well when a high humidity is provided. Especially Agathemera from high-altitude habitats are often found under stones during the day. It might well be, that females lay their eggs under these stones too. And under such stones, the micro-climate could be much more humid than in the surrounding habitat. Further experiments shall show whether a dry incubation works equally well

- another peculiar and intriguing observation is that when unhatched Agathemera luteola "Capilla del Monte" eggs have been opened up after phase 1, many of those eggs actually contained fully developed embryos. This indicates, that A. luteola embryos reach a seemingly fully developed stage rather quickly, but will remain in an inactive state and hatch a long time later on (e.g. after 1 or even 2 more years)

- nymphs start hatching about 4 - 6 weeks after the hibernation period ends

- most nymphs hatch just over a relatively short time of about 3 - 4 weeks, though some will also hatch later on. I had nymphs hatching until about mid June, when the eggs have been removed from hibernation in March. This behaviour makes sense, as there is not much time left for them to grow up and breed, before next winter will approach

Hibernation of nymphs and adults

- in their natural environment, Agathemera naturally undergo a hibernation:

- for high-altitude populations, hibernation could well last for a many months long period

- for low-land populations, hibernation could be one or several relatively short periods of lower activity or even inactivity

- an US herpetologist (working in Argentina) informed me, that he had seen Agathemera feeding even when their habitat was lightly snow-covered (in the steppe-like areas of southern Argentina)

- this observation suggests, that the hibernation of Agathemera could be interrupted by short periods of activity (including feeding), as soon as the weather warms up a bit - even during winter

- yet for CB cultures here in Europe, we do not have the food plants (Rhus, Cotinus) available during winter. Thus it is necessary to find a successful hibernation method for nymphs and adults:

- the vegetation period of Rhus and Cotinus is quite short. Rhus leaves can be used from the end of April until beginning or mid of October. While Cotinus leaves can be used from mid April until the end of October. This is quite a short time slot ... Nymphs which are hatching in May might be adult by the beginning of September. And when Rhus and Cotinus will drop their leaves again again, the oldest females have laid a few eggs only

- make sure that the fridge temperatures are at a constant (low) level. A fridge solely dedicated to this purpose is the best. Whereas a "household" fridge is most probably not suitable for Agathemera hibernation, cause it is opened regularely and thus the temperature fluctuates a lot. If temperature raise too high up, then the hibernating Agathemeras will become active too often. And this will deplete their energy reserves rather quickly, and thus they might not survive hibernation

- first hibernation test with adults (winter of 2017 / 2018)

- adults in a container (plastic cricket box) with some dry sand (1 cm deep). Few small ventilation holes (needle holes) in the box, and this box is being put in the fridge at about 8 - 11°C

- at this hibernation temperature, they were still moving around in the hibernation box. The females even produced a few eggs while under hibernation

- an adult females survived for about 2.5 months before she died, another one was already dead after 2-5 months of hibernation. On the other hand, a male survived that 2.5 months hibernation period easily, and was very agile afterwards for another 2 weeks (without food plants, which were not available in winter)

- it seems as if adult female loose their energy more quickly, as they still continue to produce a few eggs

- a 2.5 months hibernation would be not long enough, to get a culture during the European winter. This will only be possible, if the incubation period can be extended to about 6 months. That is cause their food plants won't be be available until mid or end of April

- so hopefully a lower hibernation temperature (2 - 4°C) will hopefully to the trick ...

- second hibernation test with nymphs and adults (winter 2019 / 2020)

- the goal is to hibernate them for about 6 months, until their food plants will have leaves again

- male and female nymphs and adults are placed in cricket boxes, with kitchen paper on the bottom. In a corner of the cricket box, a small sand and water filled container, which shall provide a rather high humidity

- hibernation temperature 2 - 4°C

- hibernation starts by the end of October 2019, the time when their food plant start loosing their leaves

- after 2 months of hibernation, they were all seemingly OK. They were waving their antennae when the boxes have been checked

- after 3 months of hibernation, they were still waving their antennae....

- after 4 months of hibernation, only two were still alive - a subadult female and an adult male. Both specimens were already quite weak. And with no food available for them, they would only live for another few days at RT

- during these 4 months under hibernation, the specimens stayed more or less in the same place

- the dead specimens did not appear to be emaciated

- under these conditions, a 6 months incubation of living specimens is apparently not possible

- what might have been the cause of their death? As the dead specimens did not appear to be emaciated, might it be that the temperature was too cold, or that the humidity was not high enough? Or is it just no possible to hibernate Agathemera for such a long time? More hibernation experiments are needed

- another question is, are Agathemera actually meant to hibernate? Or is it rather their eggs which hibernate? Maybe they grow up quickly so that they can lay enough eggs before next winter arrives?

Pest-potential of Agathemera luteola "Capilla del Monte" in Europe

- the natural habitat of many Agathemera populations in Argentina and Chile includes a cold and quite harsh winter period, and in many areas even temporarily snow covered. Richard D. Sage, a US herpetologist living in Argentina, reported that he had seen Agathemera in southern Argentina feeding on the leaves of a bush even in the snow (pers. comm.). This group can obviously endure harsh conditions, and thus they have some pest potential in Europe. Every breeder has to be extra careful so that that no specimen can escape to the environment. Before such cultures can be spread to other breeders, their pest potential must be tested:

- are there culture conditions which are failproof to prevent Agathemera from escaping a breeding facility? At the moment I am working on such an arrangement

- Agathemera luteola seem to be specialized feeders. So far only plants of the family Anacardiaceae could support healthy cultures. While they do also accept other food plants (see section Food Plants further up), yet they do not thrive on such plants

- do parthenogenetic eggs hatch? If not, then that would reduce their pest potential considerably. Why? Even a rather inexperienced, naive or careless breeder will take reasonable measures to make sure that specimens can't escape their cage

- and even if some specimens would escape, they will spread out in search of food plants. If some runaways (most likely small nymphs) then could survive in the wild they would be disperesed far and wide, making it unlikely that male and female meet. And thus surviving females would lay parthenogenetic eggs

- but eco-terrorism is another threat to be considered!

- can eggs, nymphs and / or adults survive when fully exposed to a winter in Europe (e.g. Switzerland)?

- more tests with local food plants are needed. If they feed and thrive well on any common european plant, this would obviously increase their pest potential for many parts of Europe. And this would speak against distributing Agathemera cultures to other breeders, to avoid that Agathemera become invasive species

Further tests with Agathemera luteola "Capilla del Monte"

- what is the connection of the clear, odorless defensive spray (adult males only?) connected with the "stinky smell" just prior to their moulting?

- are adults gregarious too?

- is a high humidity needed for a successful incubation?

Literature

- Camousseight A., Revision taxonomica del Genero Agathemera en Chile, Rev. Chilena Ent. 1995, 22: 35 - 53

- Vera, A. & A. Camousseight, 2008. Ciclo vital de Agathemera mesoauriculae, Rev. Chil. Ent. 34: 57-61

- Di Blasi E., et al. (2011). New Spiroplasma in parasitic Leptus mites and their Agathemera walking stick hosts from Argentina. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 107, 225–228.

- Schmeda-Hirschmann G. 4-methyl-l-hepten-3-one, the defensive compound from Agathemera elegans (Philippi) (Phasmatidae) Insecta. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2006;61(7-8):592-594. doi:10.1515/znc-2006-7-820

- Cubillos, C., & Vera, A. (2020).Comparative morphology of the eggs from the eight species in the genus

Agathemera Stål (Insecta: Phasmatodea), through phylogenetic comparative method approach

. Zootaxa, 4803(3), 523–543. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4803.3.8

Some basics of phasmid breeding

- our detailed notes on how to successfully breed phasmids are an integral part of this care sheet

- in order to maintain strong and healthy cultures, often 2 - 3 cages per species are needed (to keep nymphs and adults seperate)

- keep just one species per cage. Informations on why and how to keep cultures seperate and pure

- whenever one posts informations or distributes a culture to fellow breeders, then make it a point to use the full and correct scientific name with provenience affix:

- correct is for example Extatosoma tiaratum "Innisfail" - for the pure culture which originates from Innisfail

- incorrect and misleading is "prickly stick insect" for Extatosoma tiaratum, as there are many more "prickly" phasmids. Serious breeders do not use common names, as such designations only lead to confusion.

- if possible keep day temperatures below 28°C, and a nocturnal temperature drop is natural and advisable

- do not spray too often and too much, phasmids are no fish. In the confined space of a cage, with it's very limited potential for climatic balancing, humidity and moisture can quickly become too much and give raise to excessive mould and microbiologial growth